Over the winter, my husband John and I took up hiking along the Milwaukee River, just a few blocks away from where we live. We had heard a rumor from some friends about someone who had built an elaborate series of catacombs in the hillside along the river. No one seemed to know exactly where the catacombs were, but said they were built by “a crazy homeless guy” and that a newspaper article had been written about it.

Over the winter, my husband John and I took up hiking along the Milwaukee River, just a few blocks away from where we live. We had heard a rumor from some friends about someone who had built an elaborate series of catacombs in the hillside along the river. No one seemed to know exactly where the catacombs were, but said they were built by “a crazy homeless guy” and that a newspaper article had been written about it.

A few weeks ago, John and I hiked along the river again. It’s all grown over now, lush and green, but also dry because it hasn’t rained in weeks and weeks. Tall grasses rattle. The path is packed so tight it sounds hollow beneath your feet. Water levels are low and there are things laid bare in the river we’ve never seen before: large rocks, a wooden dam, cracked patches of the river’s bottom. Before taking our usual path down, John wanted to look for the catacombs and pointed to a path going the opposite way, away from the river and into the woods. We climbed up. His instincts were right. What we found were not catacombs, but – I don’t know – huts. One big one and two smaller ones. When we climbed higher to get to one of the small ones and looked down, we saw that the big one had no top. There was something triangular hanging over it from a tree.

Looking at these structures, I felt the same way I did when I stood in the middle of folk artist Loy Bowlin’s bedazzled house at the Kohler Arts Center about ten years ago. In both cases I was so overwhelmed by what the artist had done, I cried. The way the pinecones are placed in one wall of one of these huts alone is sheer genius. My photos belie the workmanship, the brilliance. They are magnificent.

When we get home I click on the link to the newspaper story, written by Crocker Stephenson for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, titled “Man builds hidden village of nests.” The first thing I see is a picture of the man who built the nests. Then I see his name. And then I realize: I know this guy.

It was last fall, when I was sent on assignment to cover one of the many organized rallies protesting Governor Scott Walker at the State Capitol in Madison, Wisconsin. I was taking the Badger Bus, which runs back and forth between Milwaukee and Madison, for the first time and feeling a little insecure about it. Paul Zasadny was sitting there waiting too, with a big canvas bag full of stuff, holding a bright blue sport drink. He assured me that I was in the right place, and that yes, the bus was always on time, and yes, it picks up right over there.

When we boarded the bus, Paul and I headed straight for the back. I took the very back seat, he took the one in front of me. We spread out. The bus took off.

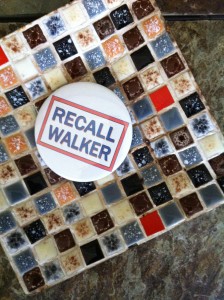

My assignment was to interview people about why they were at the rally and how they felt about Wisconsin’s political climate at the time. Paul turned halfway around in his seat and we began talking. Turns out he was heading to the rally to sell buttons, which he pronounced using a perfect alveolar stop: butt-tons. I asked him if he would care to be interviewed for the story I was working on, and the floodgates opened. He talked to me about having a disability, being on Medicare and Medicaid, and how he was afraid Governor Walker would cut these programs.

“If I get a letter in the mail saying, ‘In 30 days, you will no longer have Medicaid,'” said Paul, “what am I supposed to do?’” We talked about the East Side neighborhood of Milwaukee we both live in. Brady Street. A concert in Madison that night, where Paul would also go to sell his buttons.

“If I get a letter in the mail saying, ‘In 30 days, you will no longer have Medicaid,'” said Paul, “what am I supposed to do?’” We talked about the East Side neighborhood of Milwaukee we both live in. Brady Street. A concert in Madison that night, where Paul would also go to sell his buttons.

As we talked, he organized his wares. “We are off-balance in Wisconsin and I don’t know when we will get back in balance,” he said. “Until we do, though, I will continue to get on the bus and go to Madison. We must keep the momentum going.”

That momentum has been stunted by the the state’s recent recall election. I don’t know if the interviews I got will ever be published.

In the meantime, Paul Zasadny has built what I now know to call nests in the woods along the Milwaukee River, and I saw them with my own eyes and they are remarkable. Now that I know who he is, I can see where the same passion and vigor with which he spoke that day on the bus and peddled his buttons at the Capitol also reside in his art.

You just never know who you’re going to meet and what they’re really all about when you first set eyes on them. I knew right away that Paul Zasadny was a little different. Now I know he’s also a genius. He thanked me on the bus that day, reached into his canvas bag, and rattled around.

“Here is a butt-ton for you,” he said, holding one out to me. “For talking to me.”

Recent Comments