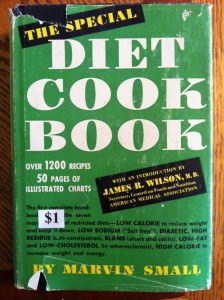

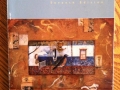

I recently purchased a few more old cookbooks, among them The Special Diet Cook Book by Marvin Small (New York: Greystone Press; 1952), which I got for a buck.

I recently purchased a few more old cookbooks, among them The Special Diet Cook Book by Marvin Small (New York: Greystone Press; 1952), which I got for a buck.

I usually pass on diet cookbooks because their look-and-feel tends to be clinical; most have no food illustrations or photographs, the hallmark of old cookbooks. There’s nothing special about The Special Diet Cook Book, other than it’s now the oldest one I own.

But there’s something else about it that makes it one of the more fascinating books I own: marginalia.

Merriam-Webster defines marginalia as “notes or embellishments (as in a book)” that a reader scrawls in the margins of a book’s pages. According to Wikipedia, Samuel Taylor Coleridge is a famous writer of marginalia. So is Voltaire, Mark Twain, Sylvia Plath, and David Foster Wallace.

As a research assistant in graduate school, I worked two semesters for a professor who studied marginalia written in late 19th-century books and magazines. Marginalia permits us to imagine a reader who engaged with a text. The notes they make in the books they read can tell us something about them, how they lived, how they read. And sometimes it can be very entertaining.

Case in point, this handwritten note that fills the inside cover of The Special Diet Cook Book (all spelling and grammar errors are the annotator’s):

“This book is not tops in diet. It cant be, as it is a cookbook to begin with and next it uses egg whites, pepper and mustard. That kills a big part of it for health diet and worse yet, vinegar and land salt too. Still its better by far then just some cookbooks. If your lucky, some time you may get Paul Braggs health cookbook. That is a much more better one. It has 402 pages, 33 pages of indexes and Prof. Paul Braggs picture in back. This costs 5 cents more, but is worth a thousand more. Its not what the doctor ordered. It tops that. It gives a vitamine chart on foods. You will see less where vinegar is left out in the other book and much white flour also land salt and not so much pepper or mustard and maybe less egg whites.”

Two more notes read: “See page 251” and “See 336.”

no images were found

Page 251 is where “The High Residue or ‘Regularity’ Diet (Anti-constipation)” chapter begins. Here is written: “This looks best.”

On page 336, where “The Low Fat – Low Cholesterol Diet” begins, “very fine” is written.

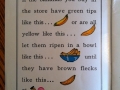

In the low fat chapter, “Yes” is written next to the recipe for “Fat-Free Whole Wheat Bread,” and “Fine” next to “Oatmeal Bread.”

“Cream of Mushroom Soup” gets an “OK.” Notes next to other recipes include “Not this” and “No,” and in some cases it’s an upper case “NO.” You can almost hear the reader shouting.

Where each “NO” appears, so does a bold “X,” right through the recipe. Under “Apricot Mustard Sauce” and “Pickled Beets,” the ingredients dry mustard and tarragon vinegar are struck through with such vehemence there’s a depression in the paper. Why the reader considered dry spice and vinegar enemies to a healthy diet, we’ll never know.

Most of the rest of the cookbook is unmarked. Did the reader have only cholesterol and constipation problems? Did the reader actually prepare the recipes? Or just read them?

In the preface is scrawled: “This book is posibly not half tops in a health cookbook. The best part is the calorie chart. Yes and no-no.”

Marginalia also indicates that the book had a few different owners. On the title page is written: “A special gift to Mr. Mrs. Senecal from L. Hollenger.” “Senecal” is crossed out and “Mr. Mrs. Morey” written in, in a different hand. It is unclear if one of the Senecals or Moreys wrote the marginalia, or if someone else did.

Whoever did, though, maybe he or she is right. Maybe it is a bad diet cookbook. Then again, maybe anger management is in order.

In either case, stuff like this is gold to storytellers. Put ten of us in a room, show us juicy little nuggets like these, and we’ll tell you ten different stories starring the Senecals, the Moreys, the book, and what happened to them. And they’ll all be good.

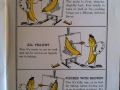

BONUS! Banana Salad Bazaar

Last spring I bought this cookbook at the Milwaukee Public Library’s bookstore because I was fascinated with the rather vitriolic notes that someone had written throughout it. I wrote an essay about it and published it here.

Last spring I bought this cookbook at the Milwaukee Public Library’s bookstore because I was fascinated with the rather vitriolic notes that someone had written throughout it. I wrote an essay about it and published it here.

Recent Comments