After I posted happy birthday wishes on our friend Josh’s Facebook wall yesterday, he wrote back and said, “I hope you’ve had a good summer.”

After I posted happy birthday wishes on our friend Josh’s Facebook wall yesterday, he wrote back and said, “I hope you’ve had a good summer.”

I told him I had. That was a lie. It wasn’t all that great.

The millions of us in the U.S. who are celebrating Labor Day this weekend are on some level probably taking stock, reflecting back on what we did over the summer, wondering if we took full advantage of the weather, the time off, the open-air activities. Labor Day is a final salute to summer, and I’m betting most of us are realizing that, no, we didn’t do everything we’d intended to do. And that because we feel disappointed and inadequate over it, we will try to cram as much as possible into this last long weekend before fall begins to set in.

The reasons my summer wasn’t all that great stem mostly from the fact that we live in an urban neighborhood, one that young people like to live in after they get their first jobs out of college, and suburbanites like to visit because it is a good place to see and be seen. Urban neighborhoods are noisy by nature, no matter what time of year. But add to the mix this summer’s oppressive heat and people flocking to Lake Michigan to seek relief, and you have more commotion than usual.

There was inordinate traffic. People who couldn’t parallel park. Driving the wrong way on one-way streets. Car horns. Every day, car horns. Residents without air conditioning sitting on stoops, trying to derive every last bit of coolness from the concrete. No rain. People partying late on the roof deck next door, people stumbling north from the bars on Brady Street and hollering at 3 a.m., people stumbling south from the bars on North Avenue and hollering at 3 a.m. One of these times, a young woman wailed and wailed outside of our building because someone stole her cell phone at a club. Her friend called her cell, the thief picked up, and said he wanted $400 for the safe return of her phone. Then hung up. More wailing.

There was inordinate traffic. People who couldn’t parallel park. Driving the wrong way on one-way streets. Car horns. Every day, car horns. Residents without air conditioning sitting on stoops, trying to derive every last bit of coolness from the concrete. No rain. People partying late on the roof deck next door, people stumbling north from the bars on Brady Street and hollering at 3 a.m., people stumbling south from the bars on North Avenue and hollering at 3 a.m. One of these times, a young woman wailed and wailed outside of our building because someone stole her cell phone at a club. Her friend called her cell, the thief picked up, and said he wanted $400 for the safe return of her phone. Then hung up. More wailing.

Garbage trucks at 5:45 a.m. on Monday morning. Utility crews jack-hammering. Someone repairing a sidewalk and jack-hammering. The lawn tools, oh, the lawn tools: leaf blowers and weed-wackers and state-of-the-art mowers that urban dwellers use on green spaces the size of one SUV. The carpet cleaners and their compressors. Public works employees who hack at trees, leaving some to look like deciduous cacti. The landscape crew of five that took a week to do work that should have taken that many people two days. Every time I went out they were on break.

I don’t know if you’ve ever seen tuckpointers in action, but they’ve been hanging off our building and the building next to ours the past four summers, using saws and drills to grind out the mortar between the bricks, and then squishing new mortar into the gaps. This summer the building next to us and the building on the other side of it have had tuckpointers working on them since late April. Every day: grind, dust, grind, dust. The guys on the building next to us play country music real loud, and the guys on the other side of them play classic rock real loud. When I threw open our bathroom window and asked the guy to turn down his country music, he wagged his finger at me and yelled, “What’s the matter with you? Don’t you like music?”

The accidents. More than I remember other summers. One occurred right in front of our building and involved six cars; a bicycle cop handled the whole thing. Accidents that, when you look at the aftermath, you can’t imagine how they happened. Who did what first? A young man on a motorcycle was hit by a car a half block away from where we live. The sound of the impact was eerie, but not half as eerie as the sound of his bike sliding across the pavement and under a parked car. It was the sound of Earth holding its breath. I will never forget it.

The accidents. More than I remember other summers. One occurred right in front of our building and involved six cars; a bicycle cop handled the whole thing. Accidents that, when you look at the aftermath, you can’t imagine how they happened. Who did what first? A young man on a motorcycle was hit by a car a half block away from where we live. The sound of the impact was eerie, but not half as eerie as the sound of his bike sliding across the pavement and under a parked car. It was the sound of Earth holding its breath. I will never forget it.

I know all this because this summer I was a homebody; I work out of our home and so can’t help that. But I also felt very introspective and didn’t want to go much of anywhere or do much of anything except to play music, write, and think.

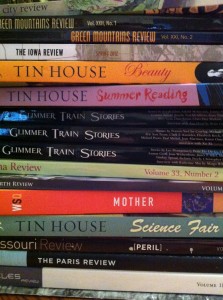

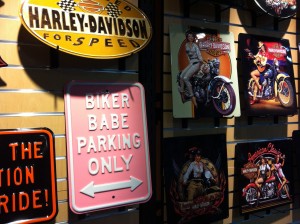

I rode my motorcycle only twice. One of those times my bike broke down. Went to only one farmer’s market and one ethnic festival. The food from which made me vomit later that night. My husband, on break from law school and bored, was underfoot. I stopped meeting with a group of friends at the German bar up the street every week; it had become too much. I called out a person who isn’t very nice who tried messing with someone I love. I lost weight, put it back on, lost it again. Did not visit the gym for a month. Slept poorly overall. Discovered that some friends aren’t the good people I was led to believe. Three rejection letters. Two potentially lucrative freelance projects severely pared back; two others placed on hold.

This commotion went on all summer long. I am happy to see it end.

But among all of these things are some stunning, gorgeous flowers in a field of weeds, as my undergrad mentor, Dr. Louis T. Milic, was fond of saying. The week after one of the most bizarre things that has ever happened to me in my professional career (I thought about writing about it here, but won’t dignify it), one of the world’s top newspapers contacted me. The writer had read something on my blog that pertained to a story she was working on and requested an interview. We talked last week and she will give me a heads-up when she knows the story is being published. Our band played its first two gigs, and we had our first professional photo shoot. I published one piece per week here. Made some nice friends in real life, on Facebook, at the bookstore, and among other writers in my community. I am finally working my way through a new essay on a topic that has been haunting me my whole life and is very difficult for me to write about.

But among all of these things are some stunning, gorgeous flowers in a field of weeds, as my undergrad mentor, Dr. Louis T. Milic, was fond of saying. The week after one of the most bizarre things that has ever happened to me in my professional career (I thought about writing about it here, but won’t dignify it), one of the world’s top newspapers contacted me. The writer had read something on my blog that pertained to a story she was working on and requested an interview. We talked last week and she will give me a heads-up when she knows the story is being published. Our band played its first two gigs, and we had our first professional photo shoot. I published one piece per week here. Made some nice friends in real life, on Facebook, at the bookstore, and among other writers in my community. I am finally working my way through a new essay on a topic that has been haunting me my whole life and is very difficult for me to write about.

And I got three new pairs of shoes. Adiós, Summer.

Torn Soul band photo by John Hauser

Recent Comments