I haven’t been writing much lately, because in January I started a full-time teaching gig. And then my students and I started lobbing the flu back and forth at each other. Most of us were sick multiple times the first half of the semester.

I haven’t been writing much lately, because in January I started a full-time teaching gig. And then my students and I started lobbing the flu back and forth at each other. Most of us were sick multiple times the first half of the semester.

Through it all, though, they and I have managed to make our way through the course: Pre-College English, a refresher on grammar and writing that prepares first-semester students for their core college English requirements—courses every student, regardless of major, must take in order to graduate.

For the first half of the semester, it is wild in the streets in my classrooms—four this semester. The students are getting the lay of the land, unsure of themselves and of the decision they have made to go to college. They are quick to verbally express their opinions, but when it comes to committing their opinions to paper, they struggle, some more than others. There is something about the blank page that brings the mightiest of my students to their knees.

I tell them that I can relate to all of their anxieties around writing and expression, because I suffer them too, and so does everyone who writes, from the beginning student to the accomplished professional. They never quite believe me though. Just last week one of my students said, “I’m not doing this,” then clenched his teeth. He looked at the computer monitor as if he wanted to vandalize it and steadfastly refused my help. I told him we could talk about it later and left him alone.

This week the log jam has broken and he is forging ahead on the project.

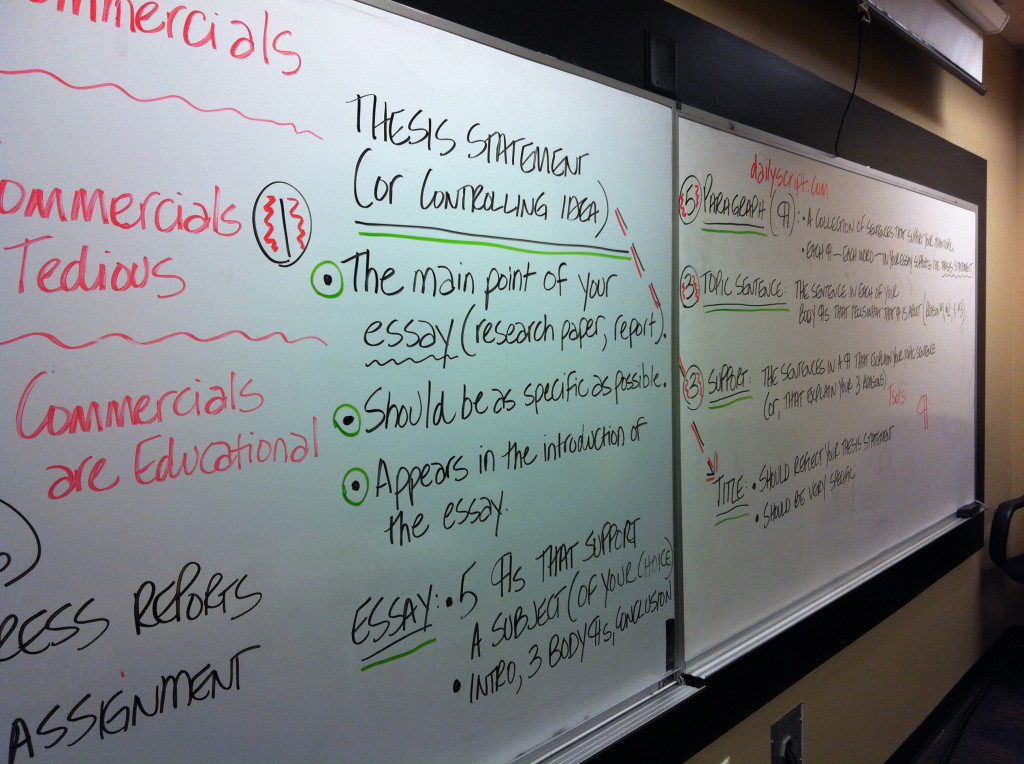

The first half of our semester is dedicated to grammar: parts of speech; mechanics; sentence structure; paragraph structure; diction; voice; flow; writing process; revision; and discourse. We talk incessantly about the connection between reading and writing, how there is a distinct difference between the way we speak and the way we write, and that one of the best ways to learn how to write better is to read more.

The first half of our semester is dedicated to grammar: parts of speech; mechanics; sentence structure; paragraph structure; diction; voice; flow; writing process; revision; and discourse. We talk incessantly about the connection between reading and writing, how there is a distinct difference between the way we speak and the way we write, and that one of the best ways to learn how to write better is to read more.

I come at my students not as a grammarian but as a writer. I tell them, “The only way you are going to get better at writing is to write.” So we do a lot of it—and reading—in my classes. Two weeks ago one of my students said, “Ms. Robin is having us write a whole book by the time this semester ends.” Which made me smile.

Where I teach, the Pre-College English course culminates in a five-paragraph argumentative essay project. In class, we talk a lot about arguing for or against an issue—and how it differs from having a verbal altercation with someone. We talk about the logic of the argument, how to write a thesis statement, topic sentences for each one of your body paragraphs that support your thesis, and an introduction and conclusion.

I don’t tell my students what to write about. “It will be a lot easier for you,” I say, “if you write about what you know, have an interest in, feel passionate about.” Whether that passion stems from love or anger, I add.

I tell them to use themselves or someone they know as examples. I show them how they can work cause-and-effect, exemplification, comparison and contrast, description, and narration into their essays. They prepare for this by reading several essays, stories, and speeches throughout the semester, responding to them, and seeing how other people express themselves.

In the five semesters I’ve taught this course, students have written the most cogent and heartfelt essays. One, a musician, made a case for the stagnant state of rap music, balanced by the signs of hope he saw emerging. Others have argued for what makes a good neighbor. Why fast food is good. Why fast food is bad. Gun control. Grandparents. Rape. Abuse. Loss.

In the five semesters I’ve taught this course, students have written the most cogent and heartfelt essays. One, a musician, made a case for the stagnant state of rap music, balanced by the signs of hope he saw emerging. Others have argued for what makes a good neighbor. Why fast food is good. Why fast food is bad. Gun control. Grandparents. Rape. Abuse. Loss.

The most stunning essay I’ve received to date is one written by a young woman whose baby was killed by her baby’s father. I never pry into my students’ lives, but I do encourage them to go deep if they want to. She wanted to. Her baby’s father, she told me, received a year’s probation for killing their child, and she wanted to argue for why he should have received a stiffer penalty.

Then she told me that her baby was killed just four months before she started school. That her mother had suggested she go to school to get her mind off of things. Every day for the rest of the semester I looked into the eyes of this beautiful child who had lost her own beautiful child just months earlier. She was elegant and intelligent and I will never forget her.

When I set out to write this, my original thought was to write a five-paragraph essay of my own as a show of camaraderie with my current students, who are aggravating over theirs right now. But I see I don’t really have room to do this now. Once again, my own writing has taken a turn, and I find myself at the end of a path I didn’t think I’d be walking.

Maybe I’ll do it another time. For now I will say:

Dear Students,

Congratulations. You have made it to the home stretch. Only three weeks left in the semester. As you make your way through the second and final drafts of your final essay project, continue to apply what you’ve learned, ask for help, stay focused. And hang in there; it will all be over soon.

I also want to thank you for everything you’re giving of yourselves this semester. And for everything you’ve taught me. In three weeks I will be sad to see you go, but I look forward to seeing you again, even if it’s only as we pass each other by in the halls. I especially look forward to seeing you at your graduation.

Have a good, restful break when this is all over. You deserve it.

Ms. Graham

On one worksheet I give my students, they practice writing simple, compound, and complex sentences. This complex sentence gets the award for being the most vivid this semester: “The dog fell into the river, while the other dog watched.”

Recent Comments