Three years ago today Greg, one of my best friends, died of a massive heart attack while teaching a weekend course in another state. One second he was alive. The next he wasn’t.

Three years ago today Greg, one of my best friends, died of a massive heart attack while teaching a weekend course in another state. One second he was alive. The next he wasn’t.

His wife Jan, also my best friend, called me the morning after it happened. While it was unusual to hear from her this time of the day and week, it wasn’t completely out of the ordinary.

“How are you?” I chirped.

“I have something to tell you,” she said. It wasn’t until she strung these six words together that I realized there was something in her voice I hadn’t ever heard in the thirty years I’d known her.

I braced myself for everything she told me next. That Greg had been in Florida. That she had talked to him the night before about her flying down to join him. That the class had reconvened Sunday morning, that he had had a heart attack, and that they had tried to save him.

“And he died,” she said, through tears.

“What?” I demanded, as if I had just been told a scandalous lie.

We cried. I said I was sorry, over and over again.

“I wanted to make sure I called,” Jan said. “I didn’t want you to find out some other way.”

After we hung up I cried hard every single day for two weeks straight.

Greg was 62 and from Jersey. Vivacious, hilarious, a smart aleck, a real character who loved music, played guitar, wrote songs, skateboarded, and roller-bladed. He saw things about life that not many of us see.

Greg was 62 and from Jersey. Vivacious, hilarious, a smart aleck, a real character who loved music, played guitar, wrote songs, skateboarded, and roller-bladed. He saw things about life that not many of us see.

Our friendship began in 1980, when Jan and I worked at Halle’s department store in Cleveland. She was the human resources manager in a branch store. I was a buyer trainee doing a year as a manager in that same store. A group of us there—Chuck, Cathy, Sheila, Bill, Jan, and I—became friendly and began socializing outside of work. Some of us started dating each other; others of us started bringing around our boyfriends and girlfriends.

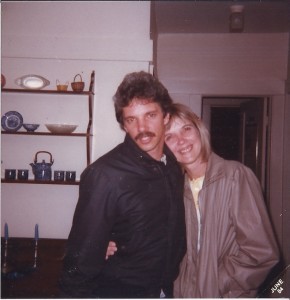

The first time I met Greg, we were all going out after work and waiting in the store for him to arrive. I have this fleeting yet vivid picture in my head of Jan leaning against a display case, smiling when he got there and as she introduced him to us. He had the most gray hair I’d ever seen on a young person, although it wasn’t anything close to the solid bright white it would become when he got older.

I don’t remember where we went that first night. But we did find out that he had a master’s degree in philosophy and worked as a janitor in a branch of the Cleveland Public Library because he didn’t live to work, he worked to live and write music and think.

Thenceforth we became a band of brothers and sisters. We took turns throwing costume parties. The best parties. I fell in love with my first husband at one of those parties. We saw live bands in The Flats, saw our first music videos at the Pirate’s Cove, and made our own music videos to Police songs.

Most of us weren’t into pot, but we did drink. Another vivid memory I have is of Greg drinking cheap rosé from one of those glass gallon jugs, which he’d hoist up on his shoulder, wind his mouth around, and chug-a-lug from. At the end of 1981 I married the man I fell in love with at Bill and Cathy’s costume party, and Jan and Greg and everyone else in our group from work were there. Greg and my husband became close friends.

I need more space to describe how dear Jan and Greg became to me over the years, and how dear they are to me today and always will be. It would take five hundred essays to adequately write about my love for them. They are two people who know me well and who loved me anyway, even during certain periods in my life when I acted a fool. They loved me unconditionally, like your mama and daddy should, and I am eternally grateful to them for that.

The irony of our collective young drinking days is that Greg put down the wine jug and went back to school to become a drug and alcohol abuse counselor. Later he also became a relationship counselor. At one particular very low point in my life during which I had no idea who I was anymore, Greg was the first person I called. He told me everything was going to be OK and recommended a colleague for me to talk to.

The irony of our collective young drinking days is that Greg put down the wine jug and went back to school to become a drug and alcohol abuse counselor. Later he also became a relationship counselor. At one particular very low point in my life during which I had no idea who I was anymore, Greg was the first person I called. He told me everything was going to be OK and recommended a colleague for me to talk to.

He recommended books to me. Music. Lots of music. He played his guitar for us on the front porch. We talked and talked and talked. Every time I came over, he and Jan had a bottle of wine for me, even though they themselves had stopped drinking.

One blazing bright sunny day in Stow, Vermont, as I was returning from the ski slopes, my cell phone rang.

“Hello?” I said.

Nothing for a whole three seconds. Then I heard Greg reciting what sounded like a poem. I realized he was reciting—rapping, really—the lines from a song on a Citizen Cope CD, which I’d recommended to him.

While he was ecstatic about Citizen Cope, he was extraordinarily pissed about Sleater Kinney, which he claimed I had also told him to get. I told him, no, I told you that I like them, but you would never like them, so shut up.

After I got divorced and moved to Milwaukee I took a new, uptight-for-no-good-reason boy home to Cleveland for Jan and Greg to meet—one of those situations in which it’s mind-blowing that these people from different phases of your life are together in one room. Greg toyed with him like my cat torments a spider. It was quite naughty and highly entertaining.

When Greg met John they fell instantly in love with each other. “He reminds me of you-know-who,” Greg said, meaning my first husband. The last time we saw Greg alive was Christmas Day 2010. He and John played guitars together that day.

Greg’s funeral was crazy-good. In his casket he had the same silly smirk he did in real life. The line for visiting hours went out the door and around the corner. An extra hour and a half had to be tacked on so that everyone who came to see him could see him.

There was a nasty rainstorm the day of the memorial service but the church was packed. We should all go out like this. We need to live our lives in ways that make people want to come out in the pouring rain and stand in hot, long-ass lines for an hour to see us for the very last time. We just do.

Four months later I went back to Cleveland to stay with Jan. I found out what had happened the day Greg died. That he had gotten his class started on an activity and then took a seat. And that after he sat down he remembered a joke he wanted to tell them. That he sprung up out of his chair and before he could speak another word, he fell to the floor. And that he was probably dead before he hit the floor.

This man who had just celebrated his wife’s birthday a week earlier. Whose doctor had just given him a clean bill of health. Who showed no signs. Alive one second. Gone the next.

On that trip Jan shared Greg’s writings with me. I never knew he wrote anything other than songs. He was an excellent writer of poetry and prose. I read page after page after page with his ashes on my lap. Jan and I went through his CDs. She told me things about him I had never known before. One of which was that he used to run on the treadmill in the basement while listening to club music—club music!—while wearing sunglasses to keep out the basement lights.

On that trip Jan shared Greg’s writings with me. I never knew he wrote anything other than songs. He was an excellent writer of poetry and prose. I read page after page after page with his ashes on my lap. Jan and I went through his CDs. She told me things about him I had never known before. One of which was that he used to run on the treadmill in the basement while listening to club music—club music!—while wearing sunglasses to keep out the basement lights.

She gave me some of his club music. When I hear it on my iPod, it makes me deliriously happy.

I don’t think he is anymore, but in the past week Greg has been around us. There was John’s Star Trek calendar, which John hadn’t gotten around to turning to March yet, which I turned to March for him. It’s on a nail with a head so thick you have to really work to get it through the hole.

Over the weekend it had been turned back to February.

Then our cats were making those I-see-a-ghost looks that cats make. “Hi, Greg,” I said, “are you here?” After which there was the strangest sound next to the coat closet, a sound I have never, ever heard in our apartment before.

The following day, when I returned home from teaching and opened the front door, something about our living room felt different. Whiter. Brighter. Longer. In an altered dimension. As if someone had moved some things or was hiding in a closet.

I set my things down and said, “I love you, Greg.”

And off he went, I like to think, to move on to the next person who knew and loved him, like Santa visiting the dreams of children the night before Christmas.

In the time it has taken me to write this essay about my dear friend, who is every bit with me as he was when he was alive, the dinner hour has come and gone. John has brought me a shot of Irish Mist, which I now raise to Greg.

I love you, Greg.

Recent Comments