I launched this website well over two years ago. It’s about time I started writing about my brothers.

In my family, I am the oldest of four children and the only girl. I have three brothers; we are all two years apart. Our mother had me when she was barely 19, and all of us by the time she was 25.

I have this memory of being taken to the hospital by my dad after one of my brothers was born. The rest of us kids were too young to be let inside to visit Mom and the new baby, so Dad walked us across the lawn and we looked up, up, up (it seemed so high at the time but the hospital was only three stories). I shielded my eyes to see her. There she was, leaning slightly out of the window and waving at us, a pin-dot in the sky. We waved back.

The only other memory I have from this period of my life is looking out a back door and seeing grass and, beyond that, thick woods. Everything was emerald green. In my mind this is Indianapolis, where we lived after Dad left the Air Force and got his first civilian job. Nowadays I wonder if I was really looking out the back door of the house my parents bought in Cleveland.

I was in my own little world during these very early years of our family. I suppose most young kids are. Once I started kindergarten my own little world burst wide open. I remember a lot about school — the smell of those big fat crayons, my teachers, pulling my underwear off with my snow pants in the coat closet — but I don’t remember much about interacting with my brothers. I do know, though, that some good seeds had to have been sown with them, because these days we are too close and like each other too much for that early period to have meant nothing.

People sometimes say to me, “I bet since you were the oldest and the only girl, you were like a little mother to them. I bet you kept them in line.”

My answer is always, “No. Far from it.”

My three brothers had a camaraderie that was special. It took root in the late 1950s and continues to this day. I was always in awe of it. They spoke a special language with each other; there were all kinds of inside jokes. They didn’t set fire to ants with a magnifying glass, but threw mashed potatoes and spaghetti noodles on the ceiling when Mom wasn’t looking. They sometimes stayed stuck up there for weeks.

My three brothers had a camaraderie that was special. It took root in the late 1950s and continues to this day. I was always in awe of it. They spoke a special language with each other; there were all kinds of inside jokes. They didn’t set fire to ants with a magnifying glass, but threw mashed potatoes and spaghetti noodles on the ceiling when Mom wasn’t looking. They sometimes stayed stuck up there for weeks.

My brothers dressed the dog in Dad’s clothes and chased her around the yard in them. They were great observers, and gave names to things that most of us aren’t even attuned to. On a family trip to Niagara Falls, they made up names for the front ends of cars like “Denny-Denny.” On trips to Pittsburgh, where our grandparents lived, a high-rise bridge along the turnpike east of Cleveland was the border between Ohio and Africa. They had names for each other like “Roast,” “Big George,” “Farmer,” “Skimp” and “Thip Stick.”

Pretending they were wearing giant berets, my brothers dashed around the house balancing the couch cushions on their heads, shouting, “I come from France!” They named the sound the swing-set made when someone swung on it too hard and it pumped out of the ground: “A-boochy-trail-ain’t-lousy-doom.” They referred to legs as “fat choppers” and hands as “meanos.”

I think that if you asked them how they came up with all these names, and all the others that aren’t even mentioned here, they would laugh and tell you they don’t exactly know. Or they might attempt to explain, then shrug, then laugh. The best creative concepts — pure imagination — can’t exactly be explained.

It might have been easy for an only sister to feel like an outsider to all this, but I never did. My brothers are smart, funny, and entertaining, and the things they say make me laugh. They made all of us laugh. They were, and still are, the reason family dinners were so much fun—and it wasn’t just because of the strand of spaghetti stuck to the ceiling by a thread over Mom’s head.

The older we got, the more at odds my middle brother and I became with each other. He was feisty and mouthy and liked to tell people what to do, and my attempts to check him backfired on a regular basis. I once wrote on the wall upstairs that I hated him, then taped something over it to hide it. When my mother found it, she gave me holy hell.

Years later, my middle brother and I realize that the reason we hated each others’ guts back then is because we were, and still are, exactly alike.

When I go back to Cleveland, I often stay with my baby brother. We have had the most amazing conversations sitting around the kitchen table. He is deep and soulful and even-tempered. He is also one of the strongest people I have ever known. He and my oldest brother are married to two of the sweetest women in the world, and they have given me two nieces and two nephews. When we get together, it’s as if we saw each other yesterday. I am immediately brought into the fold, and for this I am always grateful.

When I go back to Cleveland, I often stay with my baby brother. We have had the most amazing conversations sitting around the kitchen table. He is deep and soulful and even-tempered. He is also one of the strongest people I have ever known. He and my oldest brother are married to two of the sweetest women in the world, and they have given me two nieces and two nephews. When we get together, it’s as if we saw each other yesterday. I am immediately brought into the fold, and for this I am always grateful.

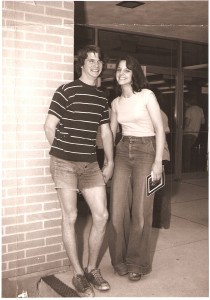

My brothers have been extraordinarily kind to the men I’ve brought home, even when there was no good reason to be. The first time they met John, they reached out and pulled him into the fold, and he’s been there ever since.

I think about my brothers every single day. I miss them very much, and more each passing year. There are times in Milwaukee when John isn’t around that I wish I could get into my car and go pay them a visit. When I was young, I used to wonder how my mother and father could go for a year or two without seeing their siblings. Now I am that person, and it bothers me.

The tradeoff for living a long life is that bad things happen. My brothers have loved, lost, survived, and started over, and so have I. The four of us are middle-aged now but our souls are young. I see it every time we get together.

Our worlds were rocked a few years ago when our mother died ten weeks after being diagnosed with cancer, and some of us have lost dear friends too. Life has taught the four of us that what we have at this moment in time may not be here tomorrow or next year. This is another thing that bothers me about being in one state while my family is in another. I’ve gained a lot these past 18 years by moving away, but I’ve missed a lot too. I want to soak in all I can. Before it changes. Again.

It always cracks me up when a reality star whose marriage proposal was just accepted says, “I am the luckiest man in the world,” or a character in a movie says, “I am the luckiest woman in the world” after she gets the gig. Although I understand the emotion behind the statement, I like to think that there are all kinds of other people in the world feeling just as lucky; there can’t be just one.

So when it comes to my brothers, I won’t say, “I am the luckiest girl in the world.” I will just say that I am unusually blessed to have not just one but three wonderful brothers.

I hope you are just as fortunate, in some kind of way. That is my fondest wish for you.

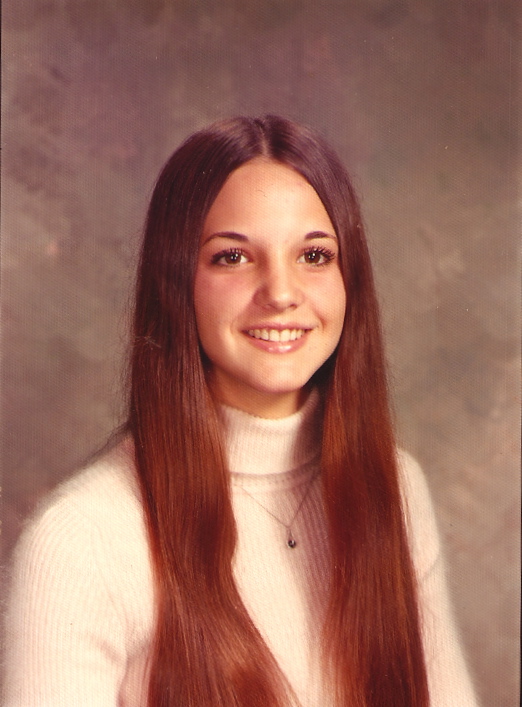

This year marks, well, let’s just say a significant anniversary of my high school graduation—one of those reunions my parents used to go to that made me wonder, “What’s the point?”

This year marks, well, let’s just say a significant anniversary of my high school graduation—one of those reunions my parents used to go to that made me wonder, “What’s the point?”

My father recently told me, “I wouldn’t blame you if you didn’t go to your reunion. The older you get, the less fun they are anyway.”

My father recently told me, “I wouldn’t blame you if you didn’t go to your reunion. The older you get, the less fun they are anyway.”

Recent Comments