I moved to Milwaukee from Cleveland fifteen and a half years ago, in early 1997. People often ask me, “So what brought you here?” and when they do I tell them “For a relationship that is no longer.” They look at me for two seconds, not sure what to do, and then all of a sudden say “Ooohh” and nod their heads.

That’s where I leave it, except with the people who are closest to me and girlfriends who ply me with five-dollar martinis at happy hour. What I will say is: all those years ago I thought I moved here for the man. But I eventually came to understand that I really moved here for myself.

When I got to Milwaukee I knew two people, and not very well. It took two years to be confident in the fact that every time I drove toward Lake Michigan I was going east, not north. I made new friends, picked up new clients. Every time I went away and came back to Milwaukee, I felt excited and happy when I saw the city limit signs, downtown, the lake.

Although I didn’t realize it until long after 1997, moving away got me away from people and situations that weren’t serving me well at all. It allowed me to grow up and become my own person.

The relationship I thought I moved here for turned out to be a disaster and ended, blessedly, ten years ago. I met John a few years afterward and my life changed again: marriage, moving from the country to the city, more new friends, travel, a motorcycle license, a master’s degree, a band. Our roots here run pretty deep.

Something in our kitchen cupboard has also driven home the fact that I am now from somewhere else: my Cleveland spices versus my Milwaukee spices.

My Cleveland spices moved here when I did. I bought them at Gust Gallucci’s, an Italian market on Cleveland’s near east side that my father and I used to swing by after shopping at the West Side Market together. Gallucci’s carried pastas I’d never heard of. Meats. Fish. Cheeses. Fresh-baked pizza. An entire aisle of olive oils. Their spices came in pint and quart containers, and were dirt-cheap: ninety-five cents for a pint of leaf thyme, a dollar fifty-one for a quart of Italian seasoning.

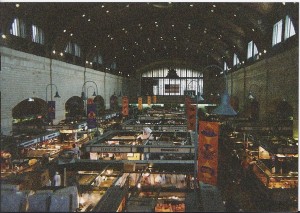

Every other Saturday morning for years, my father picked me up at 6:30 a.m. so we’d be among the first customers at the West Side Market when it opened at 7. The first thing we did was sweep the produce stands to see who had what and for what price. After the sweep we went back to the beginning, bought as much produce as we could carry, then made one trip out to the car to stash it in the trunk. Then it was time to head inside for breakfast.

To get to the indoor part of the West Side Market, where all the bakery and meat and dairy is sold, we cut through the fish stand. You have not truly lived until you’ve smelled raw fish at 7:45 on a Saturday morning, on an empty stomach and often after being at a club in The Flats until 2:30 a.m with your friends. The smell was somewhat offset by the leers you’d get from the men who worked there, scaling fish and talking in Spanish and Arabic as you walked through.

Breakfast was sandwiches and coffee from the bratwurst stand at the far end. The brats were cooked in electric skillets by three generations of one family. We ate ours on hard rolls loaded with hot mustard. I always got one to-go for my then-husband.

At the market, Dad and I got caught up with each other, and the vendors too. We’d been customers so long we saw some of the teenagers who worked there turn college graduates, thirty-somethings turn middle-aged, the middle-aged turn elderly. Breakfast was always followed by a piece of bakery—an apple fritter, Russian tea biscuit, or kolachi—which we ate as we shopped for sticks of pepperoni, small fryer chickens, pizza bagels, Lake Erie perch, dried beans, hunks of New York State sharp cheddar cheese.

When we were done, if neither of us had anything pressing to do, we drove across the bridge through downtown Cleveland and down Euclid Avenue sixty blocks to Gallucci’s. Their Web site says that this week is Frank the cashier’s 85th birthday.

I heartily recommend that anyone move away from home, just once, just for the experience. You can always go back, like my friend Sally did. Or you can stay and feel like the new place is now home, like my friend Denise. I myself vacillate between the two. Sometimes I feel more Cleveland. Sometimes I feel more Milwaukee.

Over the fifteen and a half years I’ve lived here, my Gallucci spices have worn out, dried out, and completely lost the purpose they were created for. Some are so old the containers have also dried out; when I open the plastic lids, pieces snap off and fly across the kitchen. Over the past few years they have been replaced with fresh stuff from The Spice House in downtown Milwaukee. You can smell the place a few doors away, before you even get there.

When I open our cupboard today, I see that Spice House has overrun Gallucci’s and what little Gallucci’s is left needs to be thrown out. The small bags and bottles of new spices let me know that I am from somewhere else now.

But I can still remember how the West Side market smells. The way the fresh-cut flowers bend into the aisles. Pyramids of peppers in five different colors. Iridescent drops of water on the edges of Bibb lettuce. Cookie, who has a corner produce stand and lets the ash from the cigarette that bounces in her mouth as she talks fall onto her figs and ginger root and shallots. Cookie has been dead a long time now.

But I can still remember how the West Side market smells. The way the fresh-cut flowers bend into the aisles. Pyramids of peppers in five different colors. Iridescent drops of water on the edges of Bibb lettuce. Cookie, who has a corner produce stand and lets the ash from the cigarette that bounces in her mouth as she talks fall onto her figs and ginger root and shallots. Cookie has been dead a long time now.

When someone asks me where I’m from, I say I’m from Cleveland originally but I’ve lived in Milwaukee almost sixteen years. The Gallucci spices remind me of an old life that is receding ever more deeply into the past. And of places and things and people: some still very much a part of my life, others that no longer physically exist but will always live in my heart.

The new spices remind me that I have definitely become my own person. And that I will always be grateful to Milwaukee for this.

The flowers and organic produce were grown by my brother and father at my father’s farm. My brother, the organic farmer, is also a baker, and those are his bars, cookies, and muffins.

Recent Comments